CHAPTER 8

# **Security in Computer Networks**

Way back in Section 1.6, we described some of the more prevalent and damaging classes of Internet attacks, including malware attacks, denial of service, sniffing, source masquerading, and message modification and deletion. Although we have since learned a tremendous amount about computer networks, we still haven't examined how to secure networks from those attacks. Equipped with our newly acquired expertise in computer networking and Internet protocols, we'll now study in-depth secure communication and, in particular, how computer networks can be defended from those nasty bad guys.

Let us introduce Alice and Bob, two people who want to communicate and wish to do so "securely." This being a networking text, we should remark that Alice and Bob could be two routers that want to exchange routing tables securely, a client and server that want to establish a secure transport connection, or two e-mail applications that want to exchange secure e-mail—all case studies that we will consider later in this chapter. Alice and Bob are well-known fixtures in the security community, perhaps because their names are more fun than a generic entity named "A" that wants to communicate securely with a generic entity named "B." Love affairs, wartime communication, and business transactions are the commonly cited human needs for secure communications; preferring the first to the latter two, we're happy to use Alice and Bob as our sender and receiver, and imagine them in this first scenario.

We said that Alice and Bob want to communicate and wish to do so "securely," but what precisely does this mean? As we will see, security (like love) is a manysplendored thing; that is, there are many facets to security. Certainly, Alice and Bob would like for the contents of their communication to remain secret from an eavesdropper. They probably would also like to make sure that when they are communicating, they are indeed communicating with each other, and that if their communication is tampered with by an eavesdropper, that this tampering is detected. In the first part of this chapter, we'll cover the fundamental cryptography techniques that allow for encrypting communication, authenticating the party with whom one is communicating, and ensuring message integrity.

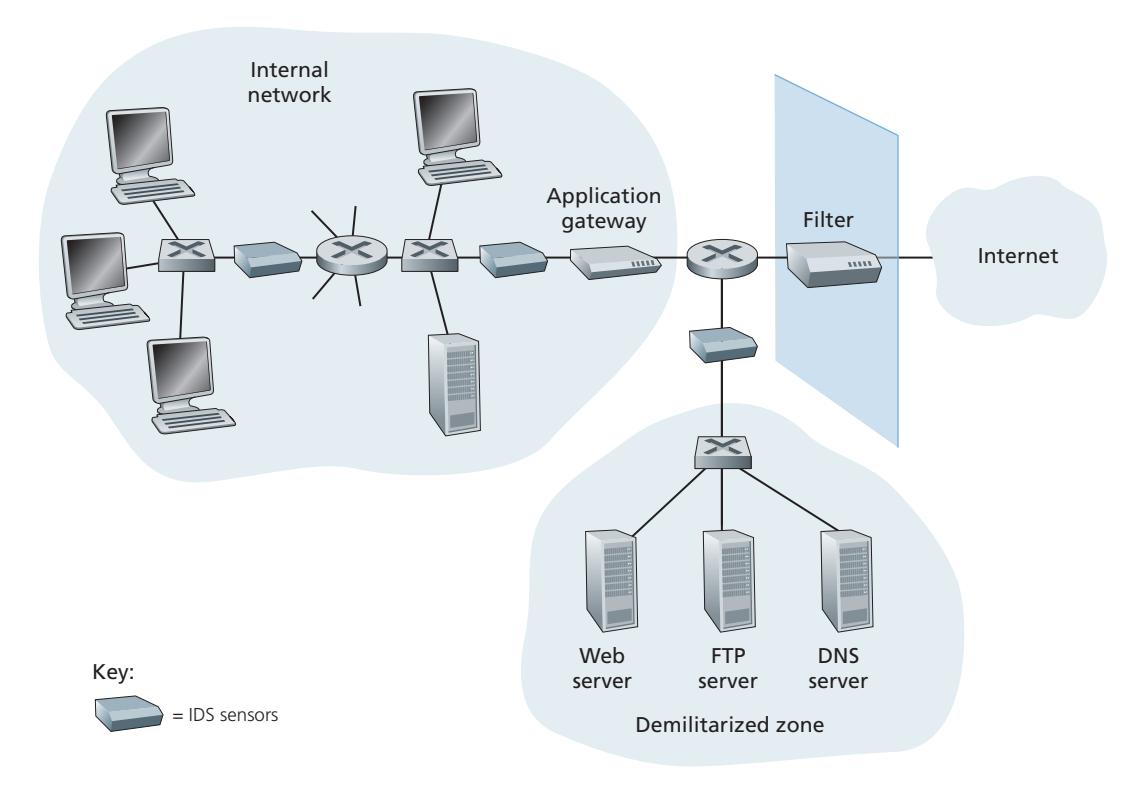

In the second part of this chapter, we'll examine how the fundamental cryptography principles can be used to create secure networking protocols. Once again taking a top-down approach, we'll examine secure protocols in each of the (top four) layers, beginning with the application layer. We'll examine how to secure e-mail, how to secure a TCP connection, how to provide blanket security at the network layer, and how to secure a wireless LAN. In the third part of this chapter we'll consider operational security, which is about protecting organizational networks from attacks. In particular, we'll take a careful look at how firewalls and intrusion detection systems can enhance the security of an organizational network.

# 8.1 **What Is Network Security?**

Let's begin our study of network security by returning to our lovers, Alice and Bob, who want to communicate "securely." What precisely does this mean? Certainly, Alice wants only Bob to be able to understand a message that she has sent, even though they *are* communicating over an insecure medium where an intruder (Trudy, the intruder) may intercept whatever is transmitted from Alice to Bob. Bob also wants to be sure that the message he receives from Alice was indeed sent by Alice, and Alice wants to make sure that the person with whom she is communicating is indeed Bob. Alice and Bob also want to make sure that the contents of their messages have not been altered in transit. They also want to be assured that they can communicate in the first place (i.e., that no one denies them access to the resources needed to communicate). Given these considerations, we can identify the following desirable properties of **secure communication**.

- *Confidentiality.* Only the sender and intended receiver should be able to understand the contents of the transmitted message. Because eavesdroppers may intercept the message, this necessarily requires that the message be somehow **encrypted** so that an intercepted message cannot be understood by an interceptor. This aspect of confidentiality is probably the most commonly perceived meaning of the term *secure communication*. We'll study cryptographic techniques for encrypting and decrypting data in Section 8.2.

- *Message integrity.* Alice and Bob want to ensure that the content of their communication is not altered, either maliciously or by accident, in transit. Extensions to the checksumming techniques that we encountered in reliable transport and data link protocols can be used to provide such message integrity. We will study message integrity in Section 8.3.

- *End-point authentication.* Both the sender and receiver should be able to confirm the identity of the other party involved in the communication—to confirm that the other party is indeed who or what they claim to be. Face-to-face human communication solves this problem easily by visual recognition. When communicating entities exchange messages over a medium where they cannot see the other party, authentication is not so simple. When a user wants to access an inbox, how does the mail server verify that the user is the person he or she claims to be? We study end-point authentication in Section 8.4.

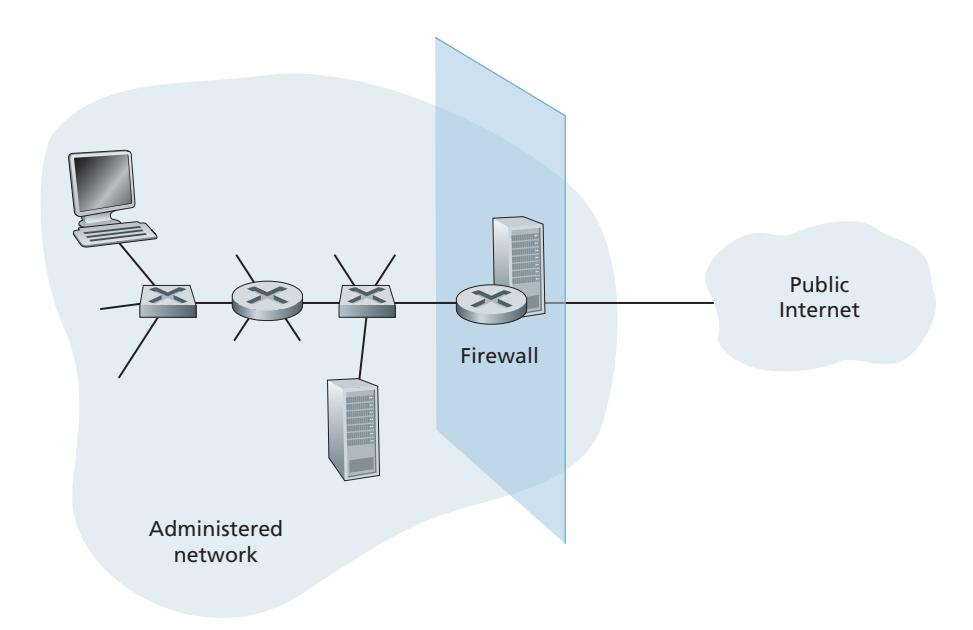

- *Operational security.* Almost all organizations (companies, universities, and so on) today have networks that are attached to the public Internet. These networks therefore can potentially be compromised. Attackers can attempt to deposit worms into the hosts in the network, obtain corporate secrets, map the internal network configurations, and launch DoS attacks. We'll see in Section 8.9 that operational devices such as firewalls and intrusion detection systems are used to counter attacks against an organization's network. A firewall sits between the organization's network and the public network, controlling packet access to and from the network. An intrusion detection system performs "deep packet inspection," alerting the network administrators about suspicious activity.

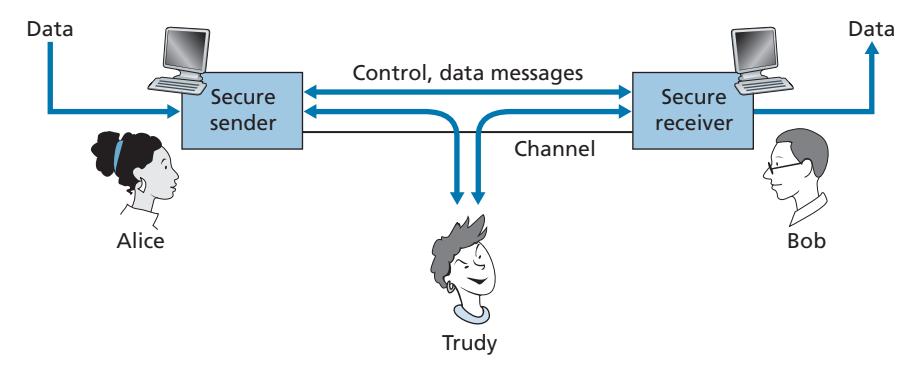

Having established what we mean by network security, let's next consider exactly what information an intruder may have access to, and what actions can be taken by the intruder. Figure 8.1 illustrates the scenario. Alice, the sender, wants to send data to Bob, the receiver. In order to exchange data securely, while meeting the requirements of confidentiality, end-point authentication, and message integrity, Alice and Bob will exchange control messages and data messages (in much the same way that TCP senders and receivers exchange control segments and data segments).

All or some of these messages will typically be encrypted. As discussed in Section 1.6, an intruder can potentially perform

- *eavesdropping*—sniffing and recording control and data messages on the channel.

- *modification, insertion*, or *deletion* of messages or message content.

As we'll see, unless appropriate countermeasures are taken, these capabilities allow an intruder to mount a wide variety of security attacks: snooping on communication (possibly stealing passwords and data), impersonating another entity, hijacking an ongoing session, denying service to legitimate network users by overloading system resources, and so on. A summary of reported attacks is maintained at the CERT Coordination Center [CERT 2020].

Having established that there are indeed real threats loose in the Internet, what are the Internet equivalents of Alice and Bob, our friends who need to communicate securely? Certainly, Bob and Alice might be human users at two end systems, for example, a real Alice and a real Bob who really do want to exchange secure e-mail. They might also be participants in an electronic commerce transaction. For example, a real Bob might want to transfer his credit card number securely to a Web server to purchase an item online. Similarly, a real Alice might want to interact with her bank online. The parties needing secure communication might themselves also be part of the network infrastructure. Recall that the domain name system (DNS, see Section 2.4) or routing daemons that exchange routing information (see Chapter 5) require secure communication between two parties. The same is true for network management applications, a topic we examined in Chapter 5). An intruder that could actively interfere with DNS lookups (as discussed in Section 2.4), routing computations (Sections 5.3 and 5.4), or network management functions (Sections 5.5 and 5.7) could wreak havoc in the Internet.

Having now established the framework, a few of the most important definitions, and the need for network security, let us next delve into cryptography. While the use of cryptography in providing confidentiality is self-evident, we'll see shortly that it is also central to providing end-point authentication and message integrity—making cryptography a cornerstone of network security.

# 8.2 **Principles of Cryptography**

Although cryptography has a long history dating back at least as far as Julius Caesar, modern cryptographic techniques, including many of those used in the Internet, are based on advances made in the past 30 years. Kahn's book, *The Codebreakers* [Kahn 1967], and Singh's book, *The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography* [Singh 1999], provide a fascinating look at the

long history of cryptography. A complete discussion of cryptography itself requires a complete book [Bishop 2003; Kaufman 2002; Schneier 2015] and so we only touch on the essential aspects of cryptography, particularly as they are practiced on the Internet. We also note that while our focus in this section will be on the use of cryptography for confidentiality, we'll see shortly that cryptographic techniques are inextricably woven into authentication, message integrity, nonrepudiation, and more.

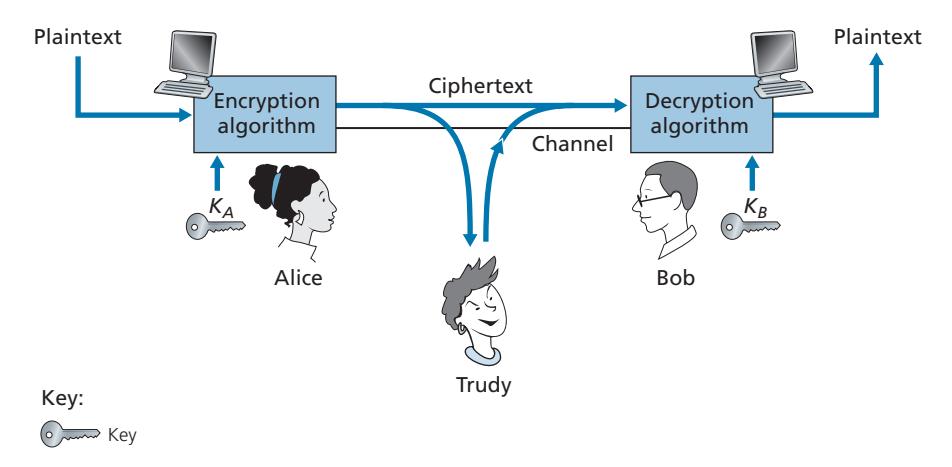

Cryptographic techniques allow a sender to disguise data so that an intruder can gain no information from the intercepted data. The receiver, of course, must be able to recover the original data from the disguised data. Figure 8.2 illustrates some of the important terminology.

Suppose now that Alice wants to send a message to Bob. Alice's message in its original form (e.g., "Bob, I love you. Alice") is known as **plaintext**, or **cleartext**. Alice encrypts her plaintext message using an **encryption algorithm** so that the encrypted message, known as **ciphertext**, looks unintelligible to any intruder. Interestingly, in many modern cryptographic systems, including those used in the Internet, the encryption technique itself is *known*—published, standardized, and available to everyone (e.g., [RFC 1321; RFC 3447; RFC 2420; NIST 2001]), even a potential intruder! Clearly, if everyone knows the method for encoding data, then there must be some secret information that prevents an intruder from decrypting the transmitted data. This is where keys come in.

In Figure 8.2, Alice provides a **key**, *KA*, a string of numbers or characters, as input to the encryption algorithm. The encryption algorithm takes the key and the plaintext message, *m*, as input and produces ciphertext as output. The notation *KA*(*m*) refers to the ciphertext form (encrypted using the key *KA*) of the plaintext message, *m*. The actual encryption algorithm that uses key *KA* will be evident from the context. Similarly, Bob will provide a key, *KB*, to the **decryption algorithm** that takes the ciphertext and Bob's key as input and produces the original plaintext as output. That is, if Bob receives an encrypted message *KA*(*m*), he decrypts it by computing *KB*(*KA*(*m*)) = *m*. In **symmetric key systems**, Alice's and Bob's keys are identical and are secret. In **public key systems**, a pair of keys is used. One of the keys is known to both Bob and Alice (indeed, it is known to the whole world). The other key is known only by either Bob or Alice (but not both). In the following two subsections, we consider symmetric key and public key systems in more detail.

# 8.2.1 **Symmetric Key Cryptography**

All cryptographic algorithms involve substituting one thing for another, for example, taking a piece of plaintext and then computing and substituting the appropriate ciphertext to create the encrypted message. Before studying a modern key-based cryptographic system, let us first get our feet wet by studying a very old, very simple symmetric key algorithm attributed to Julius Caesar, known as the **Caesar cipher** (a cipher is a method for encrypting data).

For English text, the Caesar cipher would work by taking each letter in the plaintext message and substituting the letter that is *k* letters later (allowing wraparound; that is, having the letter *z* followed by the letter *a*) in the alphabet. For example, if *k* = 3, then the letter *a* in plaintext becomes *d* in ciphertext; *b* in plaintext becomes *e* in ciphertext, and so on. Here, the value of *k* serves as the key. As an example, the plaintext message "bob, i love you. Alice" becomes "ere, l oryh brx. dolfh" in ciphertext. While the ciphertext does indeed look like gibberish, it wouldn't take long to break the code if you knew that the Caesar cipher was being used, as there are only 25 possible key values.

An improvement on the Caesar cipher is the **monoalphabetic cipher**, which also substitutes one letter of the alphabet with another letter of the alphabet. However, rather than substituting according to a regular pattern (e.g., substitution with an offset of *k* for all letters), any letter can be substituted for any other letter, as long as each letter has a unique substitute letter, and vice versa. The substitution rule in Figure 8.3 shows one possible rule for encoding plaintext.

The plaintext message "bob, i love you. Alice" becomes "nkn, s gktc wky. Mgsbc." Thus, as in the case of the Caesar cipher, this looks like gibberish. A monoalphabetic cipher would also appear to be better than the Caesar cipher in that there are 26! (on the order of 1026 ) possible pairings of letters rather than 25 possible pairings. A brute-force approach of trying all 1026 possible pairings would require far too much work to be a feasible way of breaking the encryption algorithm and decoding the message. However, by statistical analysis of the plaintext language, for example, knowing that the letters *e* and *t* are the most frequently occurring letters in typical English text (accounting for 13 percent and 9 percent of letter occurrences), and knowing that particular two-and three-letter occurrences of letters appear quite often together (for example, "in," "it," "the," "ion," "ing," and so forth) make it relatively easy to break this code. If the intruder has some knowledge about the possible contents of the message, then it is even easier to break the code. For example, if Trudy the intruder is Bob's wife and suspects Bob of having an affair with Alice, then she might suspect that the names "bob" and "alice" appear in the text. If Trudy knew for certain that those two names appeared in the ciphertext and had a copy of the example ciphertext message above, then she could immediately determine seven of the 26 letter pairings, requiring 109 fewer possibilities to be checked by a brute-force method. Indeed, if Trudy suspected Bob of having an affair, she might well expect to find some other choice words in the message as well.

```

Plaintext letter: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

Ciphertext letter: m n b v c x z a s d f g h j k l p o i u y t r e w q

```

**Figure 8.3** ♦ A monoalphabetic cipher

When considering how easy it might be for Trudy to break Bob and Alice's encryption scheme, one can distinguish three different scenarios, depending on what information the intruder has.

- *Ciphertext-only attack.* In some cases, the intruder may have access only to the intercepted ciphertext, with no certain information about the contents of the plaintext message. We have seen how statistical analysis can help in a **ciphertext-only attack** on an encryption scheme.

- *Known-plaintext attack.* We saw above that if Trudy somehow knew for sure that "bob" and "alice" appeared in the ciphertext message, then she could have determined the (plaintext, ciphertext) pairings for the letters *a, l, i, c, e, b*, and *o*. Trudy might also have been fortunate enough to have recorded all of the ciphertext transmissions and then found Bob's own decrypted version of one of the transmissions scribbled on a piece of paper. When an intruder knows some of the (plaintext, ciphertext) pairings, we refer to this as a **known-plaintext attack** on the encryption scheme.

- *Chosen-plaintext attack.* In a **chosen-plaintext attack**, the intruder is able to choose the plaintext message and obtain its corresponding ciphertext form. For the simple encryption algorithms we've seen so far, if Trudy could get Alice to send the message, "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog," she could completely break the encryption scheme. We'll see shortly that for more sophisticated encryption techniques, a chosen-plaintext attack does not necessarily mean that the encryption technique can be broken.

Five hundred years ago, techniques improving on monoalphabetic encryption, known as **polyalphabetic encryption**, were invented. The idea behind polyalphabetic encryption is to use multiple monoalphabetic ciphers, with a specific monoalphabetic cipher to encode a letter in a specific position in the plaintext message. Thus, the same letter, appearing in different positions in the plaintext message, might be encoded differently. An example of a polyalphabetic encryption scheme is shown in Figure 8.4. It has two Caesar ciphers (with *k* = 5 and *k* = 19), shown as rows. We might choose to use these two Caesar ciphers, C1 and C2, in the repeating pattern C1, C2, C2, C1, C2. That is, the first letter of plaintext is to be encoded using C1, the second and third using C2, the fourth using C1, and the fifth using C2. The pattern then repeats, with the sixth letter being encoded using C1, the seventh with C2, and so on. The plaintext message "bob, i love you." is thus encrypted "ghu, n etox dhz." Note that the first *b* in the plaintext message is encrypted using C1, while the second *b* is encrypted using C2. In this example, the encryption and decryption "key" is the knowledge of the two Caesar keys (*k* = 5, *k* = 19) and the pattern C1, C2, C2, C1, C2.

```

Plaintext letter: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

C1(k = 5):

C2(k = 19):

f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z a b c d e

t u v w x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s

```

**Figure 8.4** ♦ A polyalphabetic cipher using two Caesar ciphers

#### **Block Ciphers**

Let us now move forward to modern times and examine how symmetric key encryption is done today. We focus on block ciphers, which are used in many secure Internet protocols, including PGP (for secure e-mail), TLS (for securing TCP connections), and IPsec (for securing the network-layer transport).

In a block cipher, the message to be encrypted is processed in blocks of *k* bits. For example, if *k* = 64, then the message is broken into 64-bit blocks, and each block is encrypted independently. To encode a block, the cipher uses a one-to-one mapping to map the *k*-bit block of cleartext to a *k*-bit block of ciphertext. Let's look at an example. Suppose that *k* = 3, so that the block cipher maps 3-bit inputs (cleartext) to 3-bit outputs (ciphertext). One possible mapping is given in Table 8.1. Notice that this is a one-to-one mapping; that is, there is a different output for each input. This block cipher breaks the message up into 3-bit blocks and encrypts each block according to the above mapping. You should verify that the message 010110001111 gets encrypted into 101000111001.

Continuing with this 3-bit block example, note that the mapping in Table 8.1 is just one mapping of many possible mappings. How many possible mappings are there? To answer this question, observe that a mapping is nothing more than a permutation of all the possible inputs. There are 23 (= 8) possible inputs (listed under the input columns). These eight inputs can be permuted in 8! = 40,320 different ways. Since each of these permutations specifies a mapping, there are 40,320 possible mappings. We can view each of these mappings as a key—if Alice and Bob both know the mapping (the key), they can encrypt and decrypt the messages sent between them.

| input | output | input | output |

|-------|--------|-------|--------|

| 000 | 110 | 100 | 011 |

| 001 | 111 | 101 | 010 |

| 010 | 101 | 110 | 000 |

| 011 | 100 | 111 | 001 |

**Table 8.1** ♦ A specific 3-bit block cipher

The brute-force attack for this cipher is to try to decrypt ciphtertext by using all mappings. With only 40,320 mappings (when *k* = 3), this can quickly be accomplished on a desktop PC. To thwart brute-force attacks, block ciphers typically use much larger blocks, consisting of *k* = 64 bits or even larger. Note that the number of possible mappings for a general *k*-block cipher is 2*k* !, which is astronomical for even moderate values of *k* (such as *k* = 64).

Although full-table block ciphers, as just described, with moderate values of *k* can produce robust symmetric key encryption schemes, they are unfortunately difficult to implement. For *k* = 64 and for a given mapping, Alice and Bob would need to maintain a table with 264 input values, which is an infeasible task. Moreover, if Alice and Bob were to change keys, they would have to each regenerate the table. Thus, a full-table block cipher, providing predetermined mappings between all inputs and outputs (as in the example above), is simply out of the question.

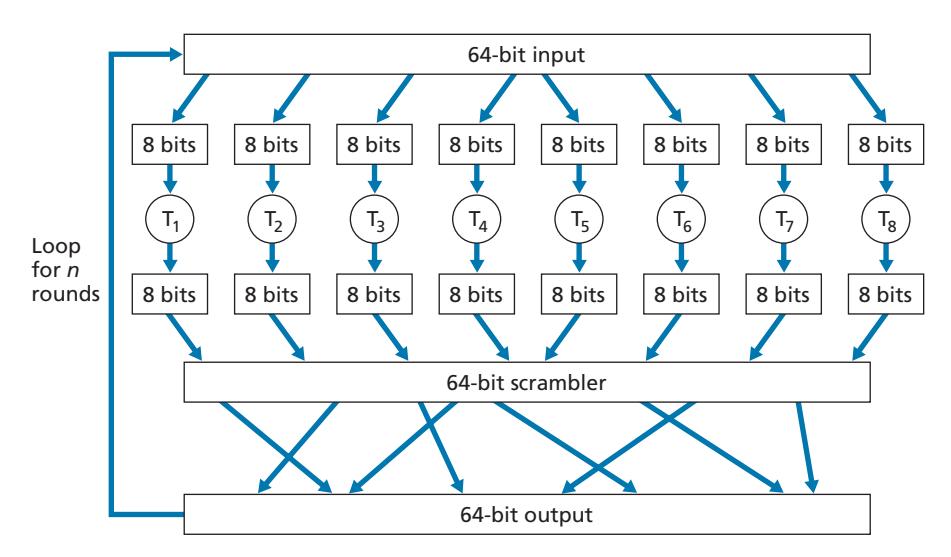

Instead, block ciphers typically use functions that simulate randomly permuted tables. An example (adapted from [Kaufman 2002]) of such a function for *k* = 64 bits is shown in Figure 8.5. The function first breaks a 64-bit block into 8 chunks, with each chunk consisting of 8 bits. Each 8-bit chunk is processed by an 8-bit to 8-bit table, which is of manageable size. For example, the first chunk is processed by the table denoted by T1. Next, the 8 output chunks are reassembled into a 64-bit block. The positions of the 64 bits in the block are then scrambled (permuted) to produce a 64-bit output. This output is fed back to the 64-bit input, where another cycle begins. After *n* such cycles, the function provides a 64-bit block of ciphertext. The purpose of the rounds is to make each input bit affect most (if not all) of the final output bits. (If only one round were used, a given input bit would affect only 8 of the 64 output bits.) The key for this block cipher algorithm would be the eight permutation tables (assuming the scramble function is publicly known).

Today there are a number of popular block ciphers, including DES (standing for Data Encryption Standard), 3DES, and AES (standing for Advanced Encryption Standard). Each of these standards uses functions, rather than predetermined tables, along the lines of Figure 8.5 (albeit more complicated and specific to each cipher). Each of these algorithms also uses a string of bits for a key. For example, DES uses 64-bit blocks with a 56-bit key. AES uses 128-bit blocks and can operate with keys that are 128, 192, and 256 bits long. An algorithm's key determines the specific "mini-table" mappings and permutations within the algorithm's internals. The bruteforce attack for each of these ciphers is to cycle through all the keys, applying the decryption algorithm with each key. Observe that with a key length of *n*, there are 2*n* possible keys. NIST [NIST 2001] estimates that a machine that could crack 56-bit DES in one second (that is, try all 256 keys in one second) would take approximately 149 trillion years to crack a 128-bit AES key.

#### **Cipher-Block Chaining**

In computer networking applications, we typically need to encrypt long messages or long streams of data. If we apply a block cipher as described by simply chopping up the message into *k*-bit blocks and independently encrypting each block, a subtle but important problem occurs. To see this, observe that two or more of the cleartext blocks can be identical. For example, the cleartext in two or more blocks could be "HTTP/1.1". For these identical blocks, a block cipher would, of course, produce the same ciphertext. An attacker could potentially guess the cleartext when it sees identical ciphertext blocks and may even be able to decrypt the entire message by identifying identical ciphtertext blocks and using knowledge about the underlying protocol structure [Kaufman 2002].

To address this problem, we can mix some randomness into the ciphertext so that identical plaintext blocks produce different ciphertext blocks. To explain this idea, let *m*(*i*) denote the *i*th plaintext block, *c*(*i*) denote the *i*th ciphertext block, and *a* ⊕ *b* denote the exclusive-or (XOR) of two bit strings, *a* and *b*. (Recall that the 0 ⊕ 0 = 1 ⊕ 1 = 0 and 0 ⊕ 1 = 1 ⊕ 0 = 1, and the XOR of two bit strings is done on a bit-by-bit basis. So, for example, 10101010 ⊕ 11110000 = 01011010.) Also, denote the block-cipher encryption algorithm with key *S* as *KS*. The basic idea is as follows. The sender creates a random *k*-bit number *r*(*i*) for the *i*th block and calculates *c*(*i*) = *KS*(*m*(*i*) ⊕ *r*(*i*)). Note that a new *k*-bit random number is chosen for each block. The sender then sends *c*(1), *r*(1), *c*(2), *r*(2), *c*(3), *r*(3), and so on. Since the receiver receives *c(i)* and *r(i)*, it can recover each block of the plaintext by computing *m*(*i*) = *KS*(*c*(*i*)) ⊕ *r*(*i*). It is important to note that, although *r*(*i*) is sent in the clear and thus can be sniffed by Trudy, she cannot obtain the plaintext *m*(*i*), since she does not know the key *KS*. Also note that if two plaintext blocks *m*(*i*) and *m*(*j*) are the same, the corresponding ciphertext blocks *c*(*i*) and *c*(*j*) will be different (as long as the random numbers *r*(*i*) and *r*(*j*) are different, which occurs with very high probability).

As an example, consider the 3-bit block cipher in Table 8.1. Suppose the plaintext is 010010010. If Alice encrypts this directly, without including the randomness, the resulting ciphertext becomes 101101101. If Trudy sniffs this ciphertext, because each of the three cipher blocks is the same, she can correctly surmise that each of the three plaintext blocks are the same. Now suppose instead Alice generates the random blocks *r*(1) = 001, *r*(2) = 111, and *r*(3) = 100 and uses the above technique to generate the ciphertext *c*(1) = 100, *c*(2) = 010, and *c*(3) = 000. Note that the three ciphertext blocks are different even though the plaintext blocks are the same. Alice then sends *c*(1), *r*(1), *c*(2), and *r*(2). You should verify that Bob can obtain the original plaintext using the shared key *KS*.

The astute reader will note that introducing randomness solves one problem but creates another: namely, Alice must transmit twice as many bits as before. Indeed, for each cipher bit, she must now also send a random bit, doubling the required bandwidth. In order to have our cake and eat it too, block ciphers typically use a technique called **Cipher Block Chaining (CBC)**. The basic idea is to send only *one random value along with the very first message, and then have the sender and receiver use the computed coded blocks in place of the subsequent random number.* Specifically, CBC operates as follows:

- 1. Before encrypting the message (or the stream of data), the sender generates a random *k*-bit string, called the **Initialization Vector (IV)**. Denote this initialization vector by *c*(0). The sender sends the IV to the receiver *in cleartext*.

- 2. For the first block, the sender calculates *m*(1) ⊕ *c*(0), that is, calculates the exclusive-or of the first block of cleartext with the IV. It then runs the result through the block-cipher algorithm to get the corresponding ciphertext block; that is, *c*(1) = *KS*(*m*(1) ⊕ *c*(0)). The sender sends the encrypted block *c*(1) to the receiver.

- 3. For the *i*th block, the sender generates the *i*th ciphertext block from *c*(*i*) = *KS*(*m*(*i*) ⊕ *c*(*i* - 1)).

Let's now examine some of the consequences of this approach. First, the receiver will still be able to recover the original message. Indeed, when the receiver receives *c*(*i*), it decrypts it with *KS* to obtain *s*(*i*) = *m*(*i*) ⊕ *c*(*i* - 1); since the receiver also knows *c*(*i* - 1), it then obtains the cleartext block from *m*(*i*) = *s*(*i*) ⊕ *c*(*i* - 1). Second, even if two cleartext blocks are identical, the corresponding ciphtertexts (almost always) will be different. Third, although the sender sends the IV in the clear, an intruder will still not be able to decrypt the ciphertext blocks, since the intruder does not know the secret key, *S*. Finally, the sender only sends one overhead block (the IV), thereby negligibly increasing the bandwidth usage for long messages (consisting of hundreds of blocks).

As an example, let's now determine the ciphertext for the 3-bit block cipher in Table 8.1 with plaintext 010010010 and IV = *c*(0) = 001. The sender first uses the IV to calculate *c*(1) = *KS*(*m*(1) ⊕ *c*(0)) = 100. The sender then calculates *c*(2) = *KS*(*m*(2) ⊕ *c*(1)) = *KS*(010 ⊕ 100) = 000, and *c*(3) = *KS*(*m*(3) ⊕ *c*(2)) = *KS*(010 ⊕ 000) = 101. The reader should verify that the receiver, knowing the IV and *KS* can recover the original plaintext.

CBC has an important consequence when designing secure network protocols: we'll need to provide a mechanism within the protocol to distribute the IV from sender to receiver. We'll see how this is done for several protocols later in this chapter.

# 8.2.2 **Public Key Encryption**

For more than 2,000 years (since the time of the Caesar cipher and up to the 1970s), encrypted communication required that the two communicating parties share a common secret—the symmetric key used for encryption and decryption. One difficulty with this approach is that the two parties must somehow agree on the shared key; but to do so in itself requires secure communication. Perhaps the parties could first meet and agree on the key in person (for example, two of Caesar's centurions might meet at the Roman baths) and thereafter communicate with encryption. In a networked world, however, communicating parties may never meet and may never converse except over the network.

Is it possible for two parties to communicate with encryption without having a shared secret key that is known in advance? In 1976, Diffie and Hellman [Diffie 1976] demonstrated an algorithm (known now as Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange) to do just that—a radically different and marvelously elegant approach toward secure communication that has led to the development of today's public key cryptography systems. We'll see shortly that public key cryptography systems also have several wonderful properties that make them useful not only for encryption, but for authentication and digital signatures as well. Interestingly, it has come to light that ideas similar to those in [Diffie 1976] and [RSA 1978] had been independently developed in the early 1970s in a series of secret reports by researchers at the Communications-Electronics Security Group in the United Kingdom [Ellis 1987].

As is often the case, great ideas can spring up independently in many places; fortunately, public key advances took place not only in private, but also in the public view, as well.

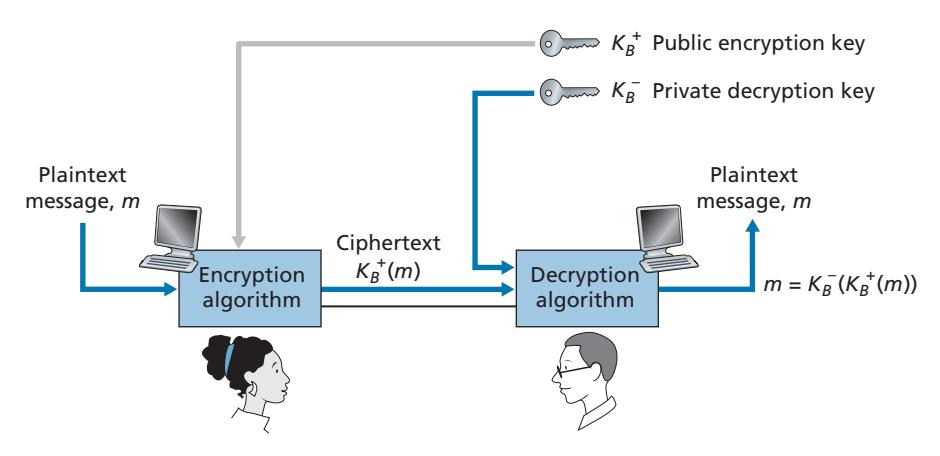

The use of public key cryptography is conceptually quite simple. Suppose Alice wants to communicate with Bob. As shown in Figure 8.6, rather than Bob and Alice sharing a single secret key (as in the case of symmetric key systems), Bob (the recipient of Alice's messages) instead has two keys—a **public key** that is available to *everyone* in the world (including Trudy the intruder) and a **private key** that is known only to Bob. We will use the notation *K*+ *B* and *K*-*B* to refer to Bob's public and private keys, respectively. In order to communicate with Bob, Alice first fetches Bob's public key. Alice then encrypts her message, *m*, to Bob using Bob's public key and a known (for example, standardized) encryption algorithm; that is, Alice computes *K*+ *B*(*m*). Bob receives Alice's encrypted message and uses his private key and a known (for example, standardized) decryption algorithm to decrypt Alice's encrypted message. That is, Bob computes *K*-*B*(*K*+ *B*(*m*)). We will see below that there are encryption/ decryption algorithms and techniques for choosing public and private keys such that *K*-*B*(*K*+ *B*(*m*)) = *m;* that is, applying Bob's public key, *K*+ *B*, to a message, *m* (to get *K*+ *B*(*m*)), and then applying Bob's private key, *K*-*B*, to the encrypted version of *m* (that is, computing *K*-*B*(*K*+ *B*(*m*))) gives back *m.* This is a remarkable result! In this manner, Alice can use Bob's publicly available key to send a secret message to Bob without either of them having to distribute any secret keys! We will see shortly that we can interchange the public key and private key encryption and get the same remarkable result––that is, *K*-*B* (*B* +(*m*)) = *K*+ *B* (*K*-*B*(*m*)) = *m*.

Although public-key cryptography is appealing, one concern immediately springs to mind. Since Bob's encryption key is public, anyone can send an encrypted message to Bob, including Alice or someone *pretending* to be Alice. In the case of a single shared secret key, the fact that the sender knows the secret key implicitly identifies the sender to the receiver. In the case of public key cryptography, however, this is no longer the case since anyone can send an encrypted message to Bob using Bob's publicly available key. A digital signature, a topic we will study in Section 8.3, is needed to bind a sender to a message.

#### **RSA**

While there may be many algorithms that address these concerns, the **RSA algorithm** (named after its founders, Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman) has become almost synonymous with public key cryptography. Let's first see how RSA works and then examine why it works.

RSA makes extensive use of arithmetic operations using modulo-*n* arithmetic. So let's briefly review modular arithmetic. Recall that *x* mod *n* simply means the remainder of *x* when divided by *n*; so, for example, 19 mod 5 = 4. In modular arithmetic, one performs the usual operations of addition, multiplication, and exponentiation. However, the result of each operation is replaced by the integer remainder that is left when the result is divided by *n*. Adding and multiplying with modular arithmetic is facilitated with the following handy facts:

```

[(a mod n) + (b mod n)] mod n = (a + b) mod n

[(a mod n) - (b mod n)] mod n = (a - b) mod n

[(a mod n) #

(b mod n)] mod n = (a # b) mod n

```

It follows from the third fact that (*a* mod *n*) *d* mod *n* = *ad* mod *n*, which is an identity that we will soon find very useful.

Now suppose that Alice wants to send to Bob an RSA-encrypted message, as shown in Figure 8.6. In our discussion of RSA, let's always keep in mind that a message is nothing but a bit pattern, and every bit pattern can be uniquely represented by an integer number (along with the length of the bit pattern). For example, suppose a message is the bit pattern 1001; this message can be represented by the decimal integer 9. Thus, when encrypting a message with RSA, it is equivalent to encrypting the unique integer number that represents the message.

There are two interrelated components of RSA:

- The choice of the public key and the private key

- The encryption and decryption algorithm

To generate the public and private RSA keys, Bob performs the following steps:

1. Choose two large prime numbers, *p* and *q*. How large should *p* and *q* be? The larger the values, the more difficult it is to break RSA, but the longer it takes to perform the encoding and decoding. RSA Laboratories recommends that the product of *p* and *q* be on the order of 1,024 bits. For a discussion of how to find large prime numbers, see [Caldwell 2020].

2. Compute *n* = *pq* and *z* = (*p* 1)(*q* 1).

3. Choose a number, *e*, less than *n*, that has no common factors (other than 1) with *z.* (In this case, *e* and *z* are said to be relatively prime.) The letter *e* is used since this value will be used in encryption.

4. Find a number, *d*, such that *ed* 1 is exactly divisible (that is, with no remainder) by *z*. The letter *d* is used because this value will be used in decryption. Put another way, given *e*, we choose *d* such that $$ed \mod z = 1$$

5. The public key that Bob makes available to the world, *K*+ *B*, is the pair of numbers (*n*, *e*); his private key, *K*-*B*, is the pair of numbers (*n*, *d*).

The encryption by Alice and the decryption by Bob are done as follows:

• Suppose Alice wants to send Bob a bit pattern represented by the integer number *m* (with *m* 6 *n*). To encode, Alice performs the exponentiation *me* , and then computes the integer remainder when *me* is divided by *n*. In other words, the encrypted value, *c*, of Alice's plaintext message, *m*, is

$$c = m^e \bmod n$$

The bit pattern corresponding to this ciphertext *c* is sent to Bob.

• To decrypt the received ciphertext message, *c*, Bob computes

$$m = c^d \bmod n$$

which requires the use of his private key (*n*, *d*).

As a simple example of RSA, suppose Bob chooses *p* = 5 and *q* = 7. (Admittedly, these values are far too small to be secure.) Then *n* = 35 and *z* = 24. Bob chooses *e* = 5, since 5 and 24 have no common factors. Finally, Bob chooses *d* = 29, since 5 # 29 - 1 (that is, *ed* - 1) is exactly divisible by 24. Bob makes the two values, *n* =35 and *e* = 5, public and keeps the value *d* = 29 secret. Observing these two public values, suppose Alice now wants to send the letters *l*, *o*, *v*, and *e* to Bob. Interpreting each letter as a number between 1 and 26 (with *a* being 1, and *z* being 26), Alice and Bob perform the encryption and decryption shown in Tables 8.2 and 8.3, respectively. Note that in this example, we consider each of the four letters as a distinct message. A more realistic example would be to convert the four letters into their 8-bit ASCII representations and then encrypt the integer corresponding to the resulting 32-bit bit pattern. (Such a realistic example generates numbers that are much too long to print in a textbook!)

| Plaintext Letter | m: numeric representation | me | me

Ciphertext c =

mod n |

|------------------|---------------------------|---------|-------------------------------|

| l | 12 | 248832 | 17 |

| o | 15 | 759375 | 15 |

| v | 22 | 5153632 | 22 |

| e | 5 | 3125 | 10 |

**Table 8.2** ♦ Alice's RSA encryption, *e* = 5, *n* = 35

Given that the "toy" example in Tables 8.2 and 8.3 has already produced some extremely large numbers, and given that we saw earlier that *p* and *q* should each be several hundred bits long, several practical issues regarding RSA come to mind. How does one choose large prime numbers? How does one then choose *e* and *d*? How does one perform exponentiation with large numbers? A discussion of these important issues is beyond the scope of this book; see [Kaufman 2002] and the references therein for details.

#### **Session Keys**

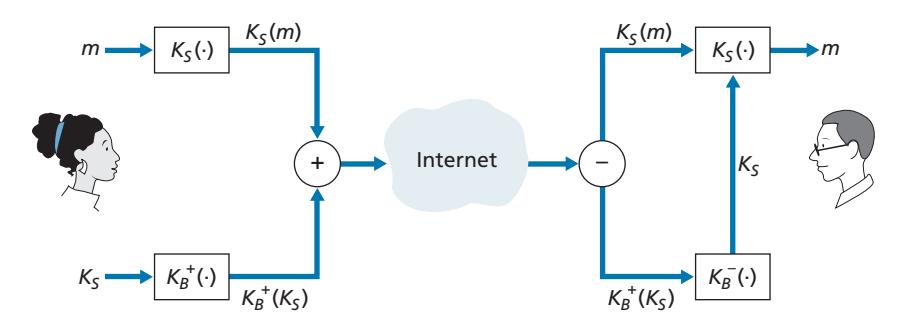

We note here that the exponentiation required by RSA is a rather time-consuming process. As a result, RSA is often used in practice in combination with symmetric key cryptography. For example, if Alice wants to send Bob a large amount of encrypted data, she could do the following. First Alice chooses a key that will be used to encode the data itself; this key is referred to as a **session key**, and is denoted by *KS*. Alice must inform Bob of the session key, since this is the shared symmetric key they will use with a symmetric key cipher (e.g., with DES or AES). Alice encrypts the session key using Bob's public key, that is, computes *c* = (*KS*) *e* mod *n*. Bob receives the RSA-encrypted session key, *c*, and decrypts it to obtain the session key, *KS*. Bob now knows the session key that Alice will use for her encrypted data transfer.

| Ciphertext c | d

c | d

m = c

mod n | Plaintext Letter |

|--------------|------------------------------------------|---------------------|------------------|

| 17 | 4819685721067509150915091411825223071697 | 12 | l |

| 15 | 127834039403948858939111232757568359375 | 15 | o |

| 22 | 851643319086537701956194499721106030592 | 22 | v |

| 10 | 1000000000000000000000000000000 | 5 | e |

**Table 8.3** ♦ Bob's RSA decryption, *d* = 29, *n* = 35

#### **Why Does RSA Work?**

RSA encryption/decryption appears rather magical. Why should it be that by applying the encryption algorithm and then the decryption algorithm, one recovers the original message? In order to understand why RSA works, again denote *n* = *pq*, where *p* and *q* are the large prime numbers used in the RSA algorithm.

Recall that, under RSA encryption, a message (uniquely represented by an integer), *m*, is exponentiated to the power *e* using modulo-*n* arithmetic, that is,

$$c = m^e \bmod n$$

Decryption is performed by raising this value to the power *d*, again using modulo-*n* arithmetic. The result of an encryption step followed by a decryption step is thus (*me* mod *n*) *d* mod *n*. Let's now see what we can say about this quantity. As mentioned earlier, one important property of modulo arithmetic is (*a* mod *n*) *d* mod *n* = *ad* mod *n* for any values *a*, *n*, and *d*. Thus, using *a* = *me* in this property, we have

$$(m^e \bmod n)^d \bmod n = m^{ed} \bmod n$$

It therefore remains to show that *med* mod *n* = *m*. Although we're trying to remove some of the magic about why RSA works, to establish this, we'll need to use a rather magical result from number theory here. Specifically, we'll need the result that says if *p* and *q* are prime, *n* = *pq*, and *z* = (*p* - 1)(*q* - 1), then *xy* mod *n* is the same as *x*(*y* mod *z*) mod *n* [Kaufman 2002]. Applying this result with *x* = *m* and *y* = *ed* we have

$$m^{ed} \mod n = m^{(ed \mod z)} \mod n$$

But remember that we have chosen *e* and *d* such that *ed* mod z = 1. This gives us

$$m^{ed} \bmod n = m^1 \bmod n = m$$

which is exactly the result we are looking for! By first exponentiating to the power of *e* (that is, encrypting) and then exponentiating to the power of *d* (that is, decrypting), we obtain the original value, *m.* Even *more* wonderful is the fact that if we first exponentiate to the power of *d* and then exponentiate to the power of *e*—that is, we reverse the order of encryption and decryption, performing the decryption operation first and then applying the encryption operation—we also obtain the original value, *m*. This wonderful result follows immediately from the modular arithmetic:

$$(m^d \bmod n)^e \bmod n = m^{de} \bmod n = m^{ed} \bmod n = (m^e \bmod n)^d \bmod n$$

The security of RSA relies on the fact that there are no known algorithms for quickly factoring a number, in this case the public value *n*, into the primes *p* and *q*. If one knew *p* and *q*, then given the public value *e*, one could easily compute the secret key, *d*. On the other hand, it is not known whether or not there *exist* fast algorithms for factoring a number, and in this sense, the security of RSA is not guaranteed. With recent advances in quantum computing, and published fast factoring algorithms for quantum computers, there are concerns that RSA may not be secure forever [MIT TR 2019]. But the practical realization of these algorithms still appears to be far in the future.

Another popular public-key encryption algorithm is the Diffie-Hellman algorithm, which we will briefly explore in the homework problems. Diffie-Hellman is not as versatile as RSA in that it cannot be used to encrypt messages of arbitrary length; it can be used, however, to establish a symmetric session key, which is in turn used to encrypt messages.

# 8.3 **Message Integrity and Digital Signatures**

In the previous section, we saw how encryption can be used to provide confidentiality to two communicating entities. In this section, we turn to the equally important cryptography topic of providing **message integrity** (also known as message authentication). Along with message integrity, we will discuss two related topics in this section: digital signatures and end-point authentication.

We define the message integrity problem using, once again, Alice and Bob. Suppose Bob receives a message (which may be encrypted or may be in plaintext) and he believes this message was sent by Alice. To authenticate this message, Bob needs to verify:

- 1. The message indeed originated from Alice.

- 2. The message was not tampered with on its way to Bob.

We'll see in Sections 8.4 through 8.7 that this problem of message integrity is a critical concern in just about all secure networking protocols.

As a specific example, consider a computer network using a link-state routing algorithm (such as OSPF) for determining routes between each pair of routers in the network (see Chapter 5). In a link-state algorithm, each router needs to broadcast a link-state message to all other routers in the network. A router's link-state message includes a list of its directly connected neighbors and the direct costs to these neighbors. Once a router receives link-state messages from all of the other routers, it can create a complete map of the network, run its least-cost routing algorithm, and configure its forwarding table. One relatively easy attack on the routing algorithm is for Trudy to distribute bogus link-state messages with incorrect link-state information. Thus, the need for message integrity—when router B receives a link-state message from router A, router B should verify that router A actually created the message and, further, that no one tampered with the message in transit.

In this section, we describe a popular message integrity technique that is used by many secure networking protocols. But before doing so, we need to cover another important topic in cryptography—cryptographic hash functions.

# 8.3.1 **Cryptographic Hash Functions**

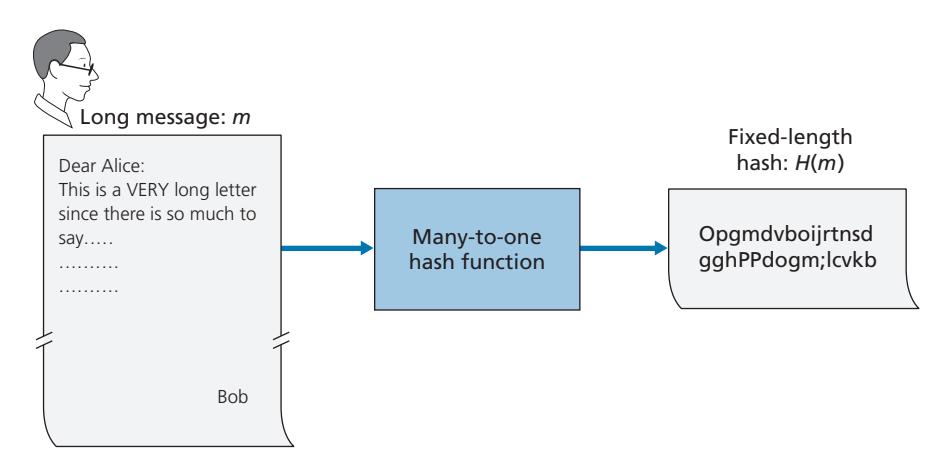

As shown in Figure 8.7, a hash function takes an input, *m*, and computes a fixed-size string *H*(*m*) known as a hash. The Internet checksum (Chapter 3) and CRCs (Chapter 6) meet this definition. A **cryptographic hash function** is required to have the following additional property:

• It is computationally infeasible to find any two different messages *x* and *y* such that *H*(*x*) = *H*(*y*).

Informally, this property means that it is computationally infeasible for an intruder to substitute one message for another message that is protected by the hash function. That is, if (*m*, *H*(*m*)) are the message and the hash of the message created by the sender, then an intruder cannot forge the contents of another message, *y*, that has the same hash value as the original message.

Let's convince ourselves that a simple checksum, such as the Internet checksum, would make a poor cryptographic hash function. Rather than performing 1s complement arithmetic (as in the Internet checksum), let us compute a checksum by treating each character as a byte and adding the bytes together using 4-byte chunks at a time. Suppose Bob owes Alice \$100.99 and sends an IOU to Alice consisting of the text string "IOU100.99BOB." The ASCII representation (in hexadecimal notation) for these letters is 49,4F,55,31,30,30,2E,39,39,42,4F,42.

Figure 8.8 (top) shows that the 4-byte checksum for this message is B2 C1 D2 AC. A slightly different message (and a much more costly one for Bob)

| | | | ASCII | | |

|---------|----|----------------|-------|----|----------|

| Message | | Representation | | | |

| IOU1 | 49 | 4F | 55 | 31 | |

| 00.9 | 30 | 30 | 2E | 39 | |

| 9BOB | 39 | 42 | 4F | 42 | |

| | B2 | C1 | D2 | AC | Checksum |

| | | | ASCII | | |

| Message | | Representation | | | |

| IOU9 | 49 | 4F | 55 | 39 | |

| 00.1 | 30 | 30 | 2E | 31 | |

| 9BOB | 39 | 42 | 4F | 42 | |

| | B2 | C1 | D2 | AC | Checksum |

**Figure 8.8** ♦ Initial message and fraudulent message have the same checksum!

is shown in the bottom half of Figure 8.8. The messages "IOU100.99BOB" and "IOU900.19BOB" have the *same* checksum. Thus, this simple checksum algorithm violates the requirement above. Given the original data, it is simple to find another set of data with the same checksum. Clearly, for security purposes, we are going to need a more powerful hash function than a checksum.

The MD5 hash algorithm of Ron Rivest [RFC 1321] is in wide use today. It computes a 128-bit hash in a four-step process consisting of a padding step (adding a one followed by enough zeros so that the length of the message satisfies certain conditions), an append step (appending a 64-bit representation of the message length before padding), an initialization of an accumulator, and a final looping step in which the message's 16-word blocks are processed (mangled) in four rounds. For a description of MD5 (including a C source code implementation) see [RFC 1321].

The second major hash algorithm in use today is the Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA-1) [FIPS 1995]. This algorithm is based on principles similar to those used in the design of MD4 [RFC 1320], the predecessor to MD5. SHA-1, a US federal standard, is required for use whenever a cryptographic hash algorithm is needed for federal applications. It produces a 160-bit message digest. The longer output length makes SHA-1 more secure.

# 8.3.2 **Message Authentication Code**

Let's now return to the problem of message integrity. Now that we understand hash functions, let's take a first stab at how we might perform message integrity:

- 1. Alice creates message *m* and calculates the hash *H*(*m*) (for example, with SHA-1).

- 2. Alice then appends *H*(*m*) to the message *m*, creating an extended message (*m*, *H*(*m*)), and sends the extended message to Bob.

- 3. Bob receives an extended message (*m*, *h*) and calculates *H*(*m*). If *H*(*m*) = *h*, Bob concludes that everything is fine.

This approach is obviously flawed. Trudy can create a bogus message *m*´ in which she says she is Alice, calculate *H*(*m*´), and send Bob (*m*´, *H*(*m*´)). When Bob receives the message, everything checks out in step 3, so Bob doesn't suspect any funny business.

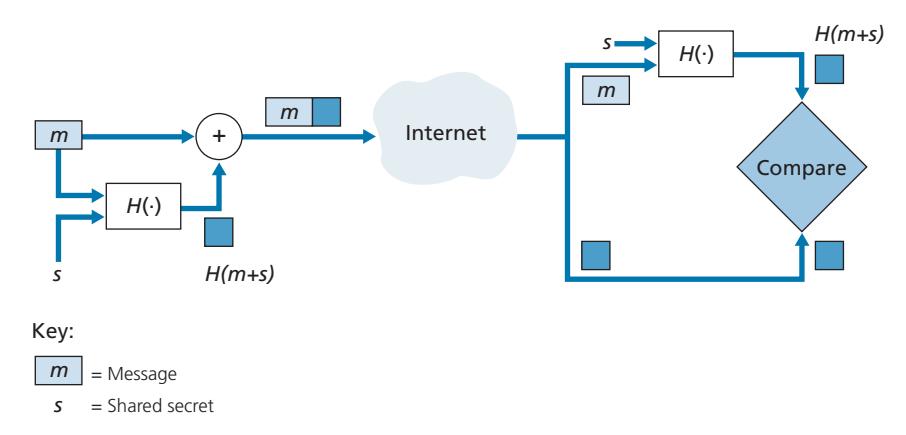

To perform message integrity, in addition to using cryptographic hash functions, Alice and Bob will need a shared secret *s*. This shared secret, which is nothing more than a string of bits, is called the **authentication key**. Using this shared secret, message integrity can be performed as follows:

- 1. Alice creates message *m*, concatenates *s* with *m* to create *m* + *s*, and calculates the hash *H*(*m* + *s*) (for example, with SHA-1). *H*(*m* + *s*) is called the **message authentication code (MAC)**.

- 2. Alice then appends the MAC to the message *m*, creating an extended message (*m, H*(*m* + *s*)), and sends the extended message to Bob.

- 3. Bob receives an extended message (*m, h*) and knowing *s*, calculates the MAC *H*(*m* + *s*). If *H*(*m* + *s*) = *h*, Bob concludes that everything is fine.

A summary of the procedure is shown in Figure 8.9. Readers should note that the MAC here (standing for "message authentication code") is not the same MAC used in link-layer protocols (standing for "medium access control")!

One nice feature of a MAC is that it does not require an encryption algorithm. Indeed, in many applications, including the link-state routing algorithm described earlier, communicating entities are only concerned with message integrity and are not concerned with message confidentiality. Using a MAC, the entities can authenticate the messages they send to each other without having to integrate complex encryption algorithms into the integrity process.

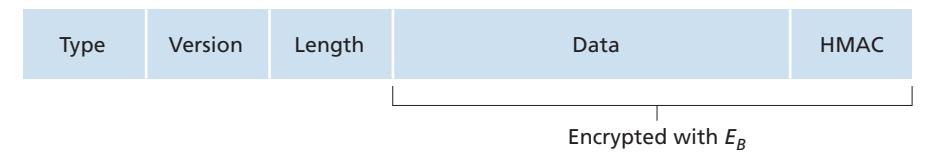

As you might expect, a number of different standards for MACs have been proposed over the years. The most popular standard today is **HMAC**, which can be used either with MD5 or SHA-1. HMAC actually runs data and the authentication key through the hash function twice [Kaufman 2002; RFC 2104].

There still remains an important issue. How do we distribute the shared authentication key to the communicating entities? For example, in the link-state routing algorithm, we would somehow need to distribute the secret authentication key to each of the routers in the autonomous system. (Note that the routers can all use the same authentication key.) A network administrator could actually accomplish this by physically visiting each of the routers. Or, if the network administrator is a lazy guy, and if each router has its own public key, the network administrator could distribute the authentication key to any one of the routers by encrypting it with the router's public key and then sending the encrypted key over the network to the router.

# 8.3.3 **Digital Signatures**

Think of the number of the times you've signed your name to a piece of paper during the last week. You sign checks, credit card receipts, legal documents, and letters. Your signature attests to the fact that you (as opposed to someone else) have acknowledged and/or agreed with the document's contents. In a digital world, one often wants to indicate the owner or creator of a document, or to signify one's agreement with a document's content. A **digital signature** is a cryptographic technique for achieving these goals in a digital world.

Just as with handwritten signatures, digital signing should be done in a way that is verifiable and nonforgeable. That is, it must be possible to prove that a document signed by an individual was indeed signed by that individual (the signature must be verifiable) and that *only* that individual could have signed the document (the signature cannot be forged).

Let's now consider how we might design a digital signature scheme. Observe that when Bob signs a message, Bob must put something on the message that is unique to him. Bob could consider attaching a MAC for the signature, where the MAC is created by appending his key (unique to him) to the message, and then taking the hash. But for Alice to verify the signature, she must also have a copy of the key, in which case the key would not be unique to Bob. Thus, MACs are not going to get the job done here.

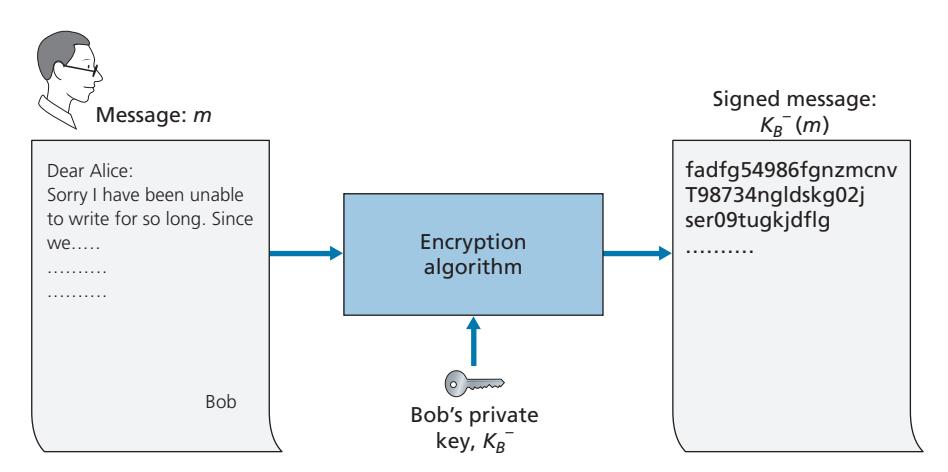

Recall that with public-key cryptography, Bob has both a public and private key, with both of these keys being unique to Bob. Thus, public-key cryptography is an excellent candidate for providing digital signatures. Let us now examine how it is done.

Suppose that Bob wants to digitally sign a document, *m*. We can think of the document as a file or a message that Bob is going to sign and send. As shown in Figure 8.10, to sign this document, Bob simply uses his private key, *K*-*B*, to compute *K*-*B*(*m*). At first, it might seem odd that Bob is using his private key (which, as we saw in Section 8.2, was used to decrypt a message that had been encrypted with his public key) to sign a document. But recall that encryption and decryption are nothing more than mathematical operations (exponentiation to the power of *e* or *d* in RSA; see Section 8.2) and recall that Bob's goal is not to scramble or obscure the contents of the document, but rather to sign the document in a manner that is verifiable and nonforgeable. Bob's digital signature of the document is *K*-*B*(*m*).

Does the digital signature *K*-*B*(*m*) meet our requirements of being verifiable and nonforgeable? Suppose Alice has *m* and *K*-*B*(*m*). She wants to prove in court (being litigious) that Bob had indeed signed the document and was the only person who could have possibly signed the document. Alice takes Bob's public key, *K*+ *B*, and applies it to the digital signature, *K*-*B*(*m*), associated with the document, *m*. That is, she computes *K*+ *B*(*K*-*B*(*m*)), and voilà, with a dramatic flurry, she produces *m*, which exactly matches the original document! Alice then argues that only Bob could have signed the document, for the following reasons:

- Whoever signed the message must have used the private key, *K*-*B*, in computing the signature *K*-*B*(*m*), such that *K*+ *B*(*K*-*B*(*m*)) = *m*.

- The only person who could have known the private key, *K*-*B*, is Bob. Recall from our discussion of RSA in Section 8.2 that knowing the public key, *K*+ *B*, is of no help in learning the private key, *K*-*B*. Therefore, the only person who could know *K*-*B* is the person who generated the pair of keys, (*K*+ *B*, *K*-*B*), in the first place, Bob. (Note that this assumes, though, that Bob has not given *K*-*B* to anyone, nor has anyone stolen *K*-*B* from Bob.)

It is also important to note that if the original document, *m*, is ever modified to some alternate form, *m*´, the signature that Bob created for *m* will not be valid for *m*´, since *K*+ *B*(*K*-*B*(*m*)) does not equal *m*´. Thus, we see that digital signatures also provide message integrity, allowing the receiver to verify that the message was unaltered as well as the source of the message.

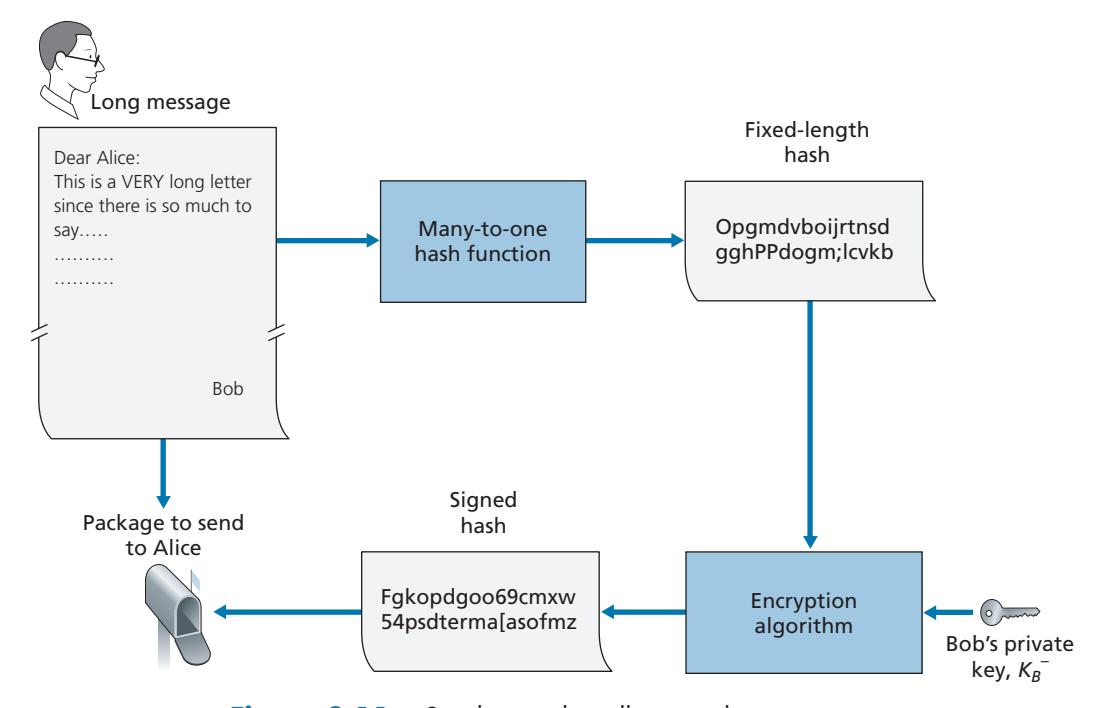

One concern with signing data by encryption is that encryption and decryption are computationally expensive. Given the overheads of encryption and decryption, signing data via complete encryption/decryption can be overkill. A more efficient approach is to introduce hash functions into the digital signature. Recall from Section 8.3.2 that a hash algorithm takes a message, *m*, of arbitrary length and computes a fixed-length "fingerprint" of the message, denoted by *H*(*m*). Using a hash function, Bob signs the hash of a message rather than the message itself, that is, Bob calculates *K*-*B*(*H*(*m*)). Since *H*(*m*) is generally much smaller than the original message *m*, the computational effort required to create the digital signature is substantially reduced.

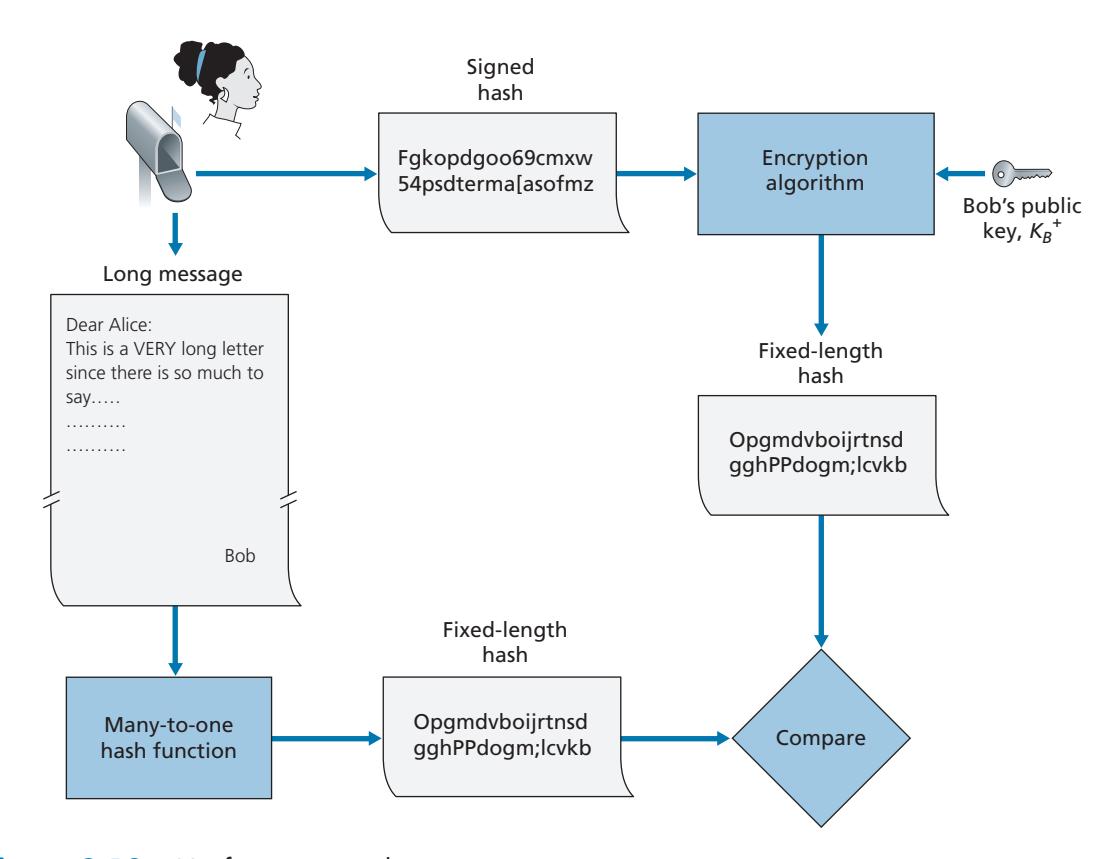

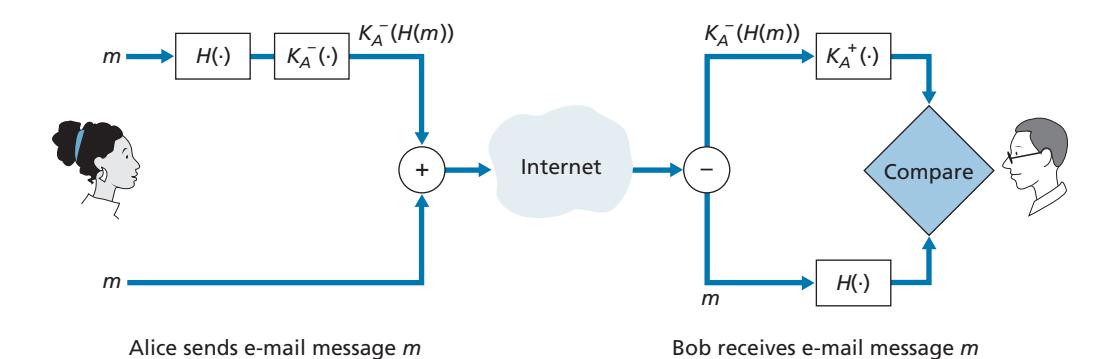

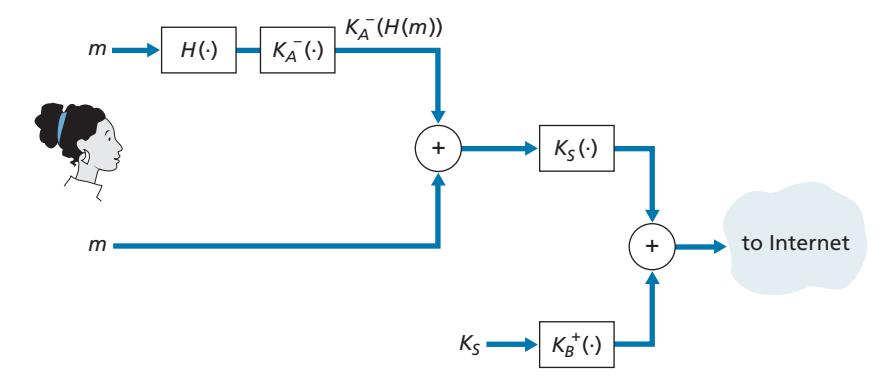

In the context of Bob sending a message to Alice, Figure 8.11 provides a summary of the operational procedure of creating a digital signature. Bob puts his original long message through a hash function. He then digitally signs the resulting hash with his private key. The original message (in cleartext) along with the digitally signed message digest (henceforth referred to as the digital signature) is then sent to Alice. Figure 8.12 provides a summary of the operational procedure of the signature. Alice applies the sender's public key to the message to obtain a hash result. Alice also applies the hash function to the cleartext message to obtain a second hash result. If the two hashes match, then Alice can be sure about the integrity and author of the message.

Before moving on, let's briefly compare digital signatures with MACs, since they have parallels, but also have important subtle differences. Both digital signatures and MACs start with a message (or a document). To create a MAC out of the message, we append an authentication key to the message, and then take the hash of the result. Note that neither public key nor symmetric key encryption is involved in creating the MAC. To create a digital signature, we first take the hash of the message and then encrypt the message with our private key (using public key cryptography). Thus, a digital signature is a "heavier" technique, since it requires an underlying Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) with certification authorities as described below. We'll see in Section 8.4 that PGP—a popular secure e-mail system—uses digital signatures for message integrity. We've seen already that OSPF uses MACs for message integrity. We'll see in Sections 8.5 and 8.6 that MACs are also used for popular transport-layer and network-layer security protocols.

#### **Public Key Certification**

An important application of digital signatures is **public key certification**, that is, certifying that a public key belongs to a specific entity. Public key certification is used in many popular secure networking protocols, including IPsec and TLS.

To gain insight into this problem, let's consider an Internet-commerce version of the classic "pizza prank." Alice is in the pizza delivery business and accepts orders over the Internet. Bob, a pizza lover, sends Alice a plaintext message that includes his home address and the type of pizza he wants. In this message, Bob also includes a digital signature (that is, a signed hash of the original plaintext message) to prove to Alice that he is the true source of the message. To verify the signature, Alice obtains Bob's public key (perhaps from a public key server or from the e-mail message) and checks the digital signature. In this manner she makes sure that Bob, rather than some adolescent prankster, placed the order.

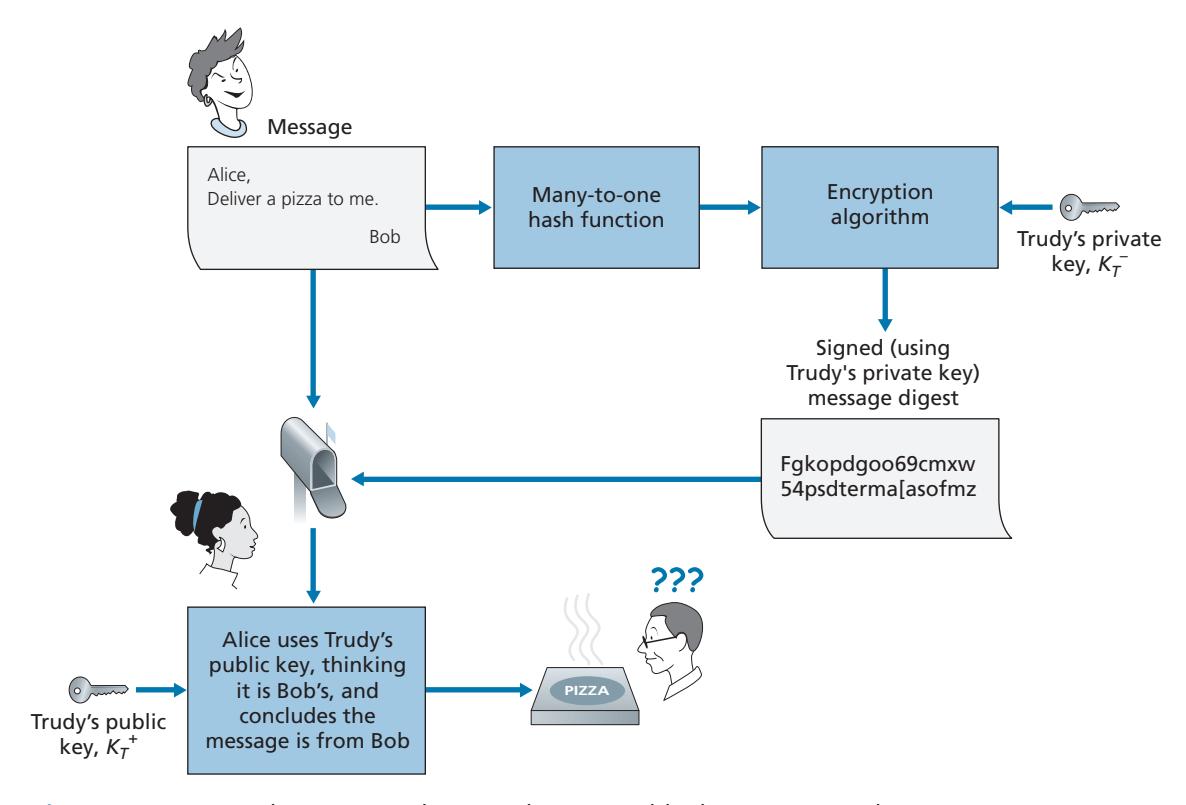

This all sounds fine until clever Trudy comes along. As shown in Figure 8.13, Trudy is indulging in a prank. She sends a message to Alice in which she says she is Bob, gives Bob's home address, and orders a pizza. In this message she also includes her (Trudy's) public key, although Alice naturally assumes it is Bob's public key. Trudy also attaches a digital signature, which was created with her own (Trudy's) private key. After receiving the message, Alice applies Trudy's public key (thinking that it is Bob's) to the digital signature and concludes that the plaintext message was indeed created by Bob. Bob will be very surprised when the delivery person brings a pizza with pepperoni and anchovies to his home!

We see from this example that for public key cryptography to be useful, you need to be able to verify that you have the actual public key of the entity (person, router, browser, and so on) with whom you want to communicate. For example, when Alice wants to communicate with Bob using public key cryptography, she needs to verify that the public key that is supposed to be Bob's is indeed Bob's.

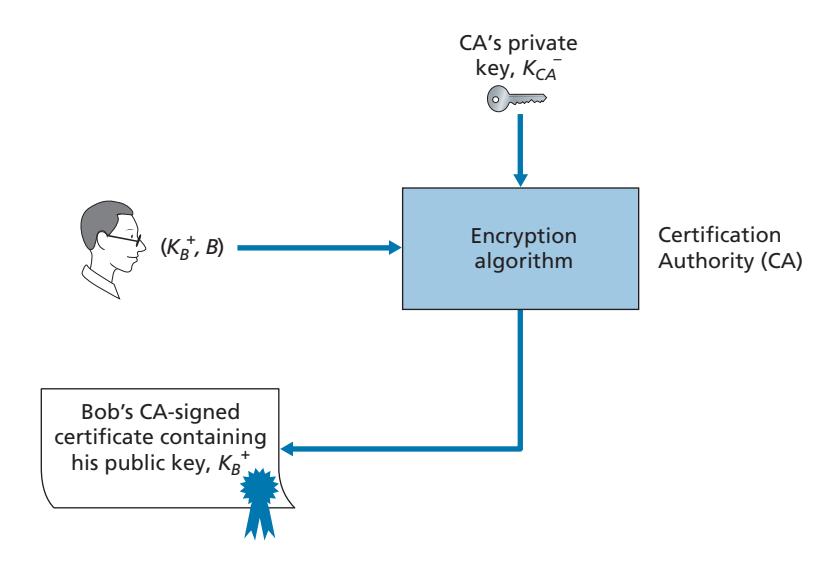

Binding a public key to a particular entity is typically done by a **Certification Authority (CA)**, whose job is to validate identities and issue certificates. A CA has the following roles:

- 1. A CA verifies that an entity (a person, a router, and so on) is who it says it is. There are no mandated procedures for how certification is done. When dealing with a CA, one must trust the CA to have performed a suitably rigorous identity verification. For example, if Trudy were able to walk into the Fly-by-Night CA and simply announce "I am Alice" and receive certificates associated with the identity of Alice, then one shouldn't put much faith in public keys certified by the Fly-by-Night CA. On the other hand, one might (or might not!) be more willing to trust a CA that is part of a federal or state program. You can trust the identity associated with a public key only to the extent to which you can trust a CA and its identity verification techniques. What a tangled web of trust we spin!

- 2. Once the CA verifies the identity of the entity, the CA creates a **certificate** that binds the public key of the entity to the identity. The certificate contains the public key and globally unique identifying information about the owner of the public key (for example, a human name or an IP address). The certificate is digitally signed by the CA. These steps are shown in Figure 8.14.

Let us now see how certificates can be used to combat pizza-ordering pranksters, like Trudy, and other undesirables. When Bob places his order he also sends his CA-signed certificate. Alice uses the CA's public key to check the validity of Bob's certificate and extract Bob's public key.

Both the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the IETF have developed standards for CAs. ITU X.509 [ITU 2005a] specifies an authentication service as well as a specific syntax for certificates. [RFC 1422] describes CAbased key management for use with secure Internet e-mail. It is compatible with X.509 but goes beyond X.509 by establishing procedures and conventions for a key management architecture. Table 8.4 describes some of the important fields in a certificate.

| Description |

|--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| |

| Version number of X.509 specification |

| CA-issued unique identifier for a certificate |

| Specifies the algorithm used by CA to sign this certificate |

| Identity of CA issuing this certificate, in distinguished name (DN) [RFC 4514] format |

| Start and end of period of validity for certificate |

| Identity of entity whose public key is associated with this certificate, in DN format |

| The subject's public key as well indication of the public key algorithm (and algorithm

parameters) to be used with this key |

| |

**Table 8.4** ♦ Selected fields in an X.509 and RFC 1422 public key

# 8.4 **End-Point Authentication**

**End-point authentication** is the process of one entity proving its identity to another entity over a computer network, for example, a user proving its identity to an e-mail server. As humans, we authenticate each other in many ways: We recognize each other's faces when we meet, we recognize each other's voices on the telephone, we are authenticated by the customs official who checks us against the picture on our passport.

In this section, we consider how one party can authenticate another party when the two are communicating over a network. We focus here on authenticating a "live" party, at the point in time when communication is actually occurring. A concrete example is a user authenticating him or herself to an e-mail server. This is a subtly different problem from proving that a message received at some point in the past did indeed come from that claimed sender, as studied in Section 8.3.

When performing authentication over the network, the communicating parties cannot rely on biometric information, such as a visual appearance or a voiceprint. Indeed, we will see in our later case studies that it is often network elements such as routers and client/server processes that must authenticate each other. Here, authentication must be done solely on the basis of messages and data exchanged as part of an **authentication protocol**. Typically, an authentication protocol would run *before* the two communicating parties run some other protocol (for example, a reliable data transfer protocol, a routing information exchange protocol, or an e-mail protocol). The authentication protocol first establishes the identities of the parties to each other's satisfaction; only after authentication do the parties get down to the work at hand.

As in the case of our development of a reliable data transfer (rdt) protocol in Chapter 3, we will find it instructive here to develop various versions of an authentication protocol, which we will call **ap** (authentication protocol), and poke holes in each version as we proceed. (If you enjoy this stepwise evolution of a design, you might also enjoy [Bryant 1988], which recounts a fictitious narrative between designers of an opennetwork authentication system, and their discovery of the many subtle issues involved.)

Let's assume that Alice needs to authenticate herself to Bob.

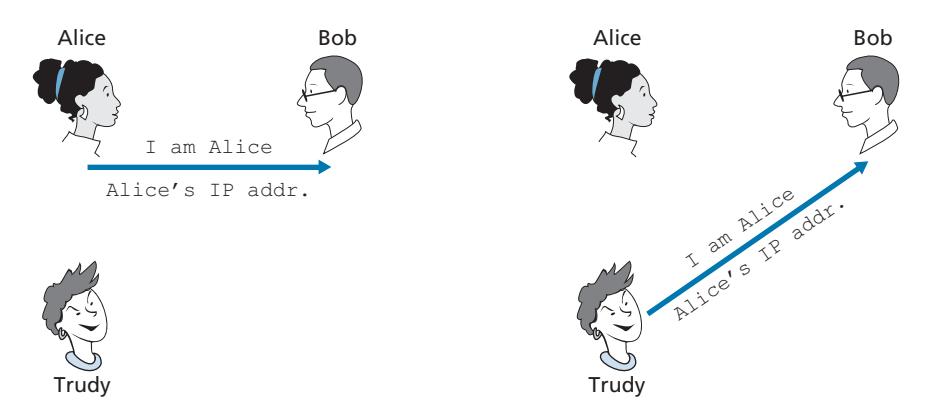

Perhaps the simplest authentication protocol we can imagine is one where Alice simply sends a message to Bob saying she is Alice. This protocol is shown in Figure 8.15. The flaw here is obvious—there is no way for Bob actually to know that the person sending the message "I am Alice" is indeed Alice. For example, Trudy (the intruder) could just as well send such a message.

#### **Authentication Protocol** *ap2.0*

If Alice has a well-known network address (e.g., an IP address) from which she always communicates, Bob could attempt to authenticate Alice by verifying that the source address on the IP datagram carrying the authentication message matches Alice's well-known address. In this case, Alice would be authenticated. This might stop a very network-naive intruder from impersonating Alice, but it wouldn't stop the determined student studying this book, or many others!

From our study of the network and data link layers, we know that it is not that hard (for example, if one had access to the operating system code and could build one's own operating system kernel, as is the case with Linux and several other freely available operating systems) to create an IP datagram, put whatever IP source address we want (for example, Alice's well-known IP address) into the IP datagram, and send the datagram over the link-layer protocol to the first-hop router. From then on, the incorrectly source-addressed datagram would be dutifully forwarded to Bob. This approach, shown in Figure 8.16, is a form of IP spoofing. IP spoofing can be avoided if Trudy's first-hop router is configured to forward only datagrams containing Trudy's IP source address [RFC 2827]. However, this capability is not universally deployed or enforced. Bob would thus be foolish to assume that Trudy's network manager (who might be Trudy herself) had configured Trudy's first-hop router to forward only appropriately addressed datagrams.

#### **Authentication Protocol** *ap3.0*

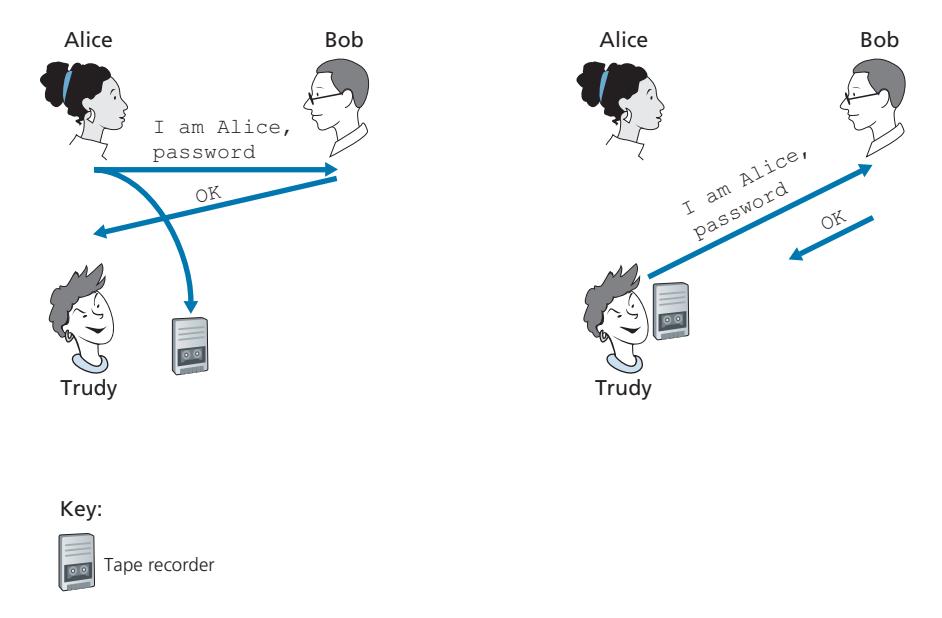

One classic approach to authentication is to use a secret password. The password is a shared secret between the authenticator and the person being authenticated. Gmail, Facebook, telnet, FTP, and many other services use password authentication. In protocol ap3.0, Alice thus sends her secret password to Bob, as shown in Figure 8.17.

Since passwords are so widely used, we might suspect that protocol *ap3.0* is fairly secure. If so, we'd be wrong! The security flaw here is clear. If Trudy eavesdrops on Alice's communication, then she can learn Alice's password. Lest you think this is unlikely, consider the fact that when you Telnet to another machine and log in, the login password is sent unencrypted to the Telnet server. Someone connected to the Telnet client or server's LAN can possibly sniff (read and store) all packets transmitted on the LAN and thus steal the login password. In fact, this is a wellknown approach for stealing passwords (see, for example, [Jimenez 1997]). Such a threat is obviously very real, so *ap3.0* clearly won't do.

#### **Authentication Protocol** *ap3.1*

Our next idea for fixing ap3.0 is naturally to encrypt the password. By encrypting the password, we can prevent Trudy from learning Alice's password. If we assume that Alice and Bob share a symmetric secret key, *KA*-*B*, then Alice can encrypt the password and send her identification message, "I am Alice," and her encrypted password to Bob. Bob then decrypts the password and, assuming the password is correct, authenticates Alice. Bob feels comfortable in authenticating Alice since Alice not only knows the password, but also knows the shared secret key value needed to encrypt the password. Let's call this protocol *ap3.1*.

While it is true that *ap3.1* prevents Trudy from learning Alice's password, the use of cryptography here does not solve the authentication problem. Bob is subject to a **playback attack**: Trudy need only eavesdrop on Alice's communication, record the encrypted version of the password, and play back the encrypted version of the password to Bob to pretend that she is Alice. The use of an encrypted password in *ap3.1* doesn't make the situation manifestly different from that of protocol *ap3.0* in Figure 8.17.

#### **Authentication Protocol** *ap4.0*

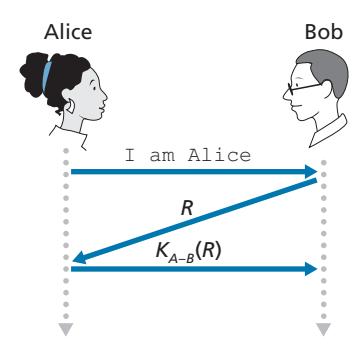

The failure scenario in Figure 8.17 resulted from the fact that Bob could not distinguish between the original authentication of Alice and the later playback of Alice's original authentication. That is, Bob could not tell if Alice was live (that is, was currently really on the other end of the connection) or whether the messages he was receiving were a recorded playback of a previous authentication of Alice. The very (*very*) observant reader will recall that the three-way TCP handshake protocol needed to address the same problem—the server side of a TCP connection did not want to accept a connection if the received SYN segment was an old copy (retransmission) of a SYN segment from an earlier connection. How did the TCP server side solve the problem of determining whether the client was really live? It chose an initial sequence number that had not been used in a very long time, sent that number to the client, and then waited for the client to respond with an ACK segment containing that number. We can adopt the same idea here for authentication purposes.

A **nonce** is a number that a protocol will use only once in a lifetime. That is, once a protocol uses a nonce, it will never use that number again. Our *ap4.0* protocol uses a nonce as follows:

- 1. Alice sends the message "I am Alice" to Bob.

- 2. Bob chooses a nonce, R, and sends it to Alice.

- 3. Alice encrypts the nonce using Alice and Bob's symmetric secret key, *KA*-*B*, and sends the encrypted nonce, *KA*-*B* (R), back to Bob. As in protocol *ap3.1*, it is the fact that Alice knows *KA*-*B* and uses it to encrypt a value that lets Bob know that the message he receives was generated by Alice. The nonce is used to ensure that Alice is live.

- 4. Bob decrypts the received message. If the decrypted nonce equals the nonce he sent Alice, then Alice is authenticated.

Protocol *ap4.0* is illustrated in Figure 8.18. By using the once-in-a-lifetime value, *R*, and then checking the returned value, *KA*-*B* (*R*), Bob can be sure that Alice is both who she says she is (since she knows the secret key value needed to encrypt *R)* and live (since she has encrypted the nonce, *R*, that Bob just created).

The use of a nonce and symmetric key cryptography forms the basis of *ap4.0*. A natural question is whether we can use a nonce and public key cryptography (rather than symmetric key cryptography) to solve the authentication problem. This issue is explored in the problems at the end of the chapter.

# 8.5 **Securing E-Mail**

In previous sections, we examined fundamental issues in network security, including symmetric key and public key cryptography, end-point authentication, key distribution, message integrity, and digital signatures. We are now going to examine how these tools are being used to provide security in the Internet.

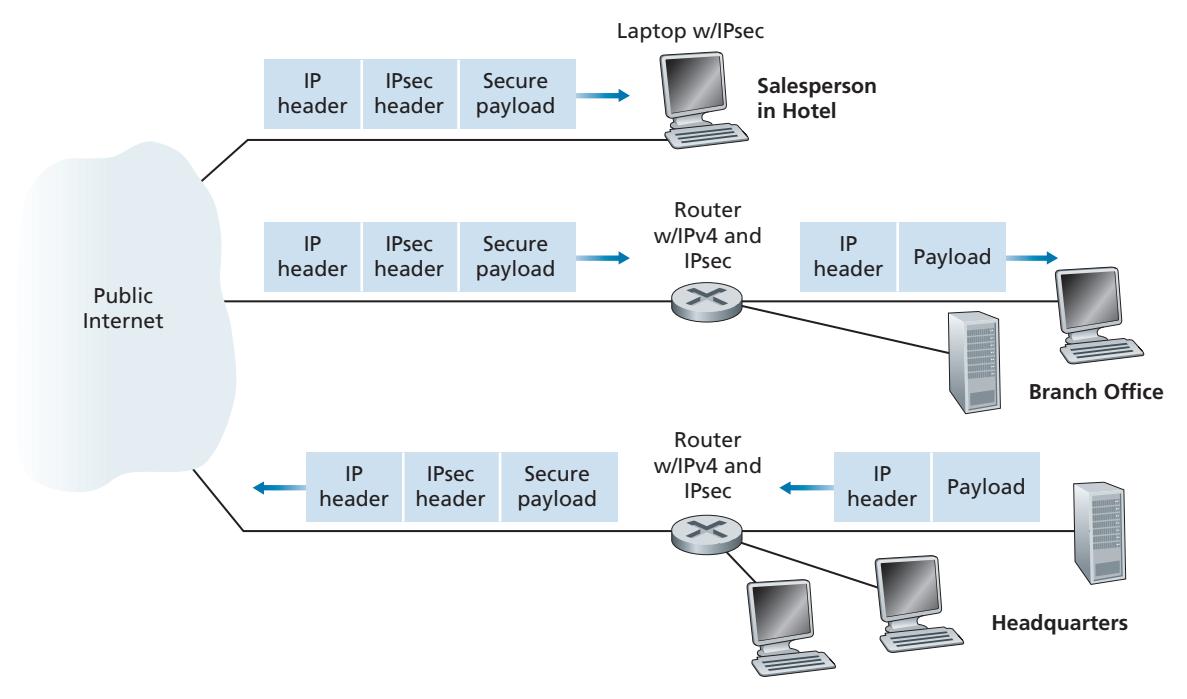

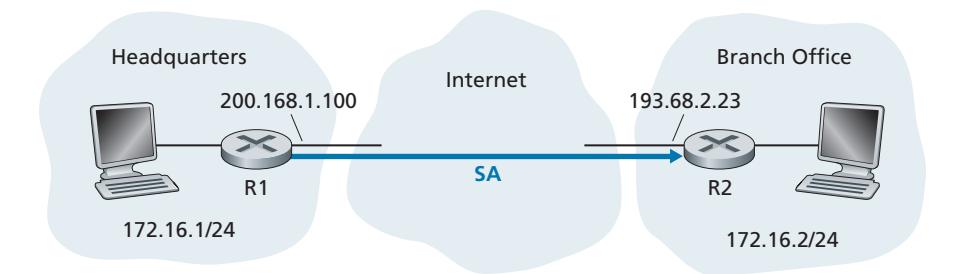

Interestingly, it is possible to provide security services in any of the top four layers of the Internet protocol stack. When security is provided for a specific application-layer protocol, the application using the protocol will enjoy one or more security services, such as confidentiality, authentication, or integrity. When security is provided for a transport-layer protocol, all applications that use that protocol enjoy the security services of the transport protocol. When security is provided at the network layer on a host-to-host basis, all transport-layer segments (and hence all applicationlayer data) enjoy the security services of the network layer. When security is provided on a link basis, then the data in all frames traveling over the link receive the security services of the link.

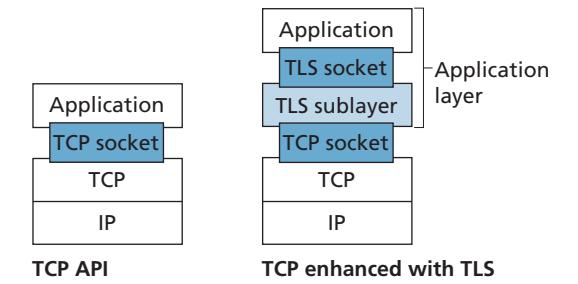

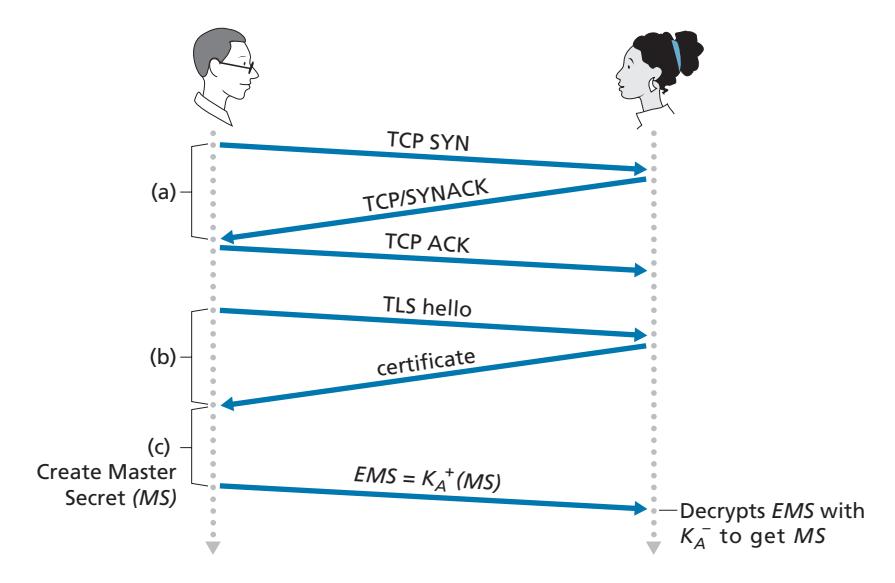

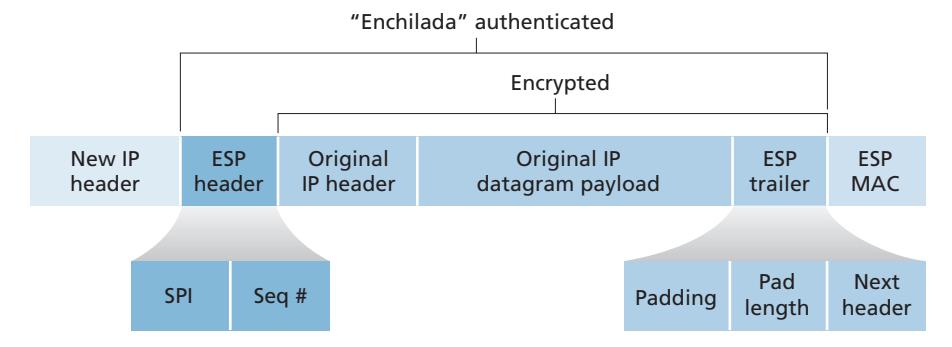

In Sections 8.5 through 8.8, we examine how security tools are being used in the application, transport, network, and link layers. Being consistent with the general structure of this book, we begin at the top of the protocol stack and discuss security at the application layer. Our approach is to use a specific application, e-mail, as a case study for application-layer security. We then move down the protocol stack. We'll examine the TLS protocol (which provides security at the transport layer), IPsec (which provides security at the network layer), and the security of the IEEE 802.11 wireless LAN protocol.

You might be wondering why security functionality is being provided at more than one layer in the Internet. Wouldn't it suffice simply to provide the security functionality at the network layer and be done with it? There are two answers to this question. First, although security at the network layer can offer "blanket coverage" by encrypting all the data in the datagrams (that is, all the transport-layer segments) and by authenticating all the source IP addresses, it can't provide user-level security. For example, a commerce site cannot rely on IP-layer security to authenticate a customer who is purchasing goods at the commerce site. Thus, there is a need for security functionality at higher layers as well as blanket coverage at lower layers. Second, it is generally easier to deploy new Internet services, including security services, at the higher layers of the protocol stack. While waiting for security to be broadly deployed at the network layer, which is probably still many years in the future, many application developers "just do it" and introduce security functionality into their favorite applications. A classic example is Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), which provides secure e-mail (discussed later in this section). Requiring only client and server application code, PGP was one of the first security technologies to be broadly used in the Internet.

# 8.5.1 **Secure E-Mail**

We now use the cryptographic principles of Sections 8.2 through 8.3 to create a secure e-mail system. We create this high-level design in an incremental manner, at each step introducing new security services. When designing a secure e-mail system, let us keep in mind the racy example introduced in Section 8.1—the love affair between Alice and Bob. Imagine that Alice wants to send an e-mail message to Bob, and Trudy wants to intrude.